How to avoid getting caught out by short sellers

For the vast majority of investors, short selling is a discipline that’s at odds with their own investing approach. Most will usually buy shares with the expectation that they’ll rise in price rather than short sell them in the hope they’ll fall. Not only that, but attempting to profit from falling share prices can incur high trading costs and the risk of big financial losses. But some investors, such as hedge funds, specialise in finding shares to short sell, which means they have to be some of the smartest stock pickers around.

By knowing which shares they are shorting (and how aggressively they are shorting them) you can avoid potentially dangerous stocks, but also profit from rocketing share prices when they get it wrong.

What is short selling?

To sell a stock short, a ‘shorter’ first has to borrow shares from someone who owns them and then sell them into the market. They are now short and will aim to buy the shares back at a lower price to make a profit.

If the stock price rises the short seller will lose money, and because share prices can keep rising there is a theoretical risk of infinite losses. For this reason, short sellers may need very deep pockets, a strong appetite for risk and a long investment horizon before their bets come good.

Borrowing shares generates ongoing costs in the form of interest payments to the lender so the short seller has to be certain that the share price will fall. Generally, it is only institutional investors with large research departments that are able to find the edge needed to be sure their short positions will work.

In an interview with Columbia Business School’s investment newsletter Graham & Doddsville, Jim Chanos, a famous short seller and founder of hedge fund Kynikos Associates, explained:

You’re basically told that you’re wrong in every way imaginable every day. It takes a certain type of individual to drown that noise and negative reinforcement out and to remind oneself that their work is accurate and what they’re hearing is not.

Given the conviction needed to be a successful short seller, it’s unsurprising that academic studies have found that heavily shorted stocks do underperform the market by a considerable margin. This is exacerbated when you consider that the act of short selling can itself be a magnet to other short sellers, who join the trade and push the price down further.

How to measure how much shorting is going on in your stocks

While hedge funds generally keep their research a secret from curious onlookers, their short positions must be disclosed to the market regulator by law. In the UK the data is published in an arcane spreadsheet deep on the Financial Conduct Authority’s website. Here, hedge funds are obliged to record changes in their positions on an ongoing basis. From this data shrewd investors can compile several key metrics:

1. Short Interest

If you divide the number of shares being short sold by the number of shares outstanding in a company you can find the level of ‘short interest’ - usually expressed as a percentage. As an example, if 12.5m shares are short sold in a company with 100m shares outstanding, the short interest would be 12.5%.

In the UK market only about 15% of shares are being short sold at any one time and the range of short interest levels can vary between 0% and 15%. In general, the higher the short interest, the more negative the short selling sentiment is about the stock. But there’s no need to be immediately frightened by a stock with short interest of just a few percent. Research shows that stocks with low short interest can often outperform, but high short interest is a major red flag[1].

For long-only investors, profiting from short interest data can be a simple as sticking to buying shares with no or low levels of short interest and avoiding shares with high short interest.

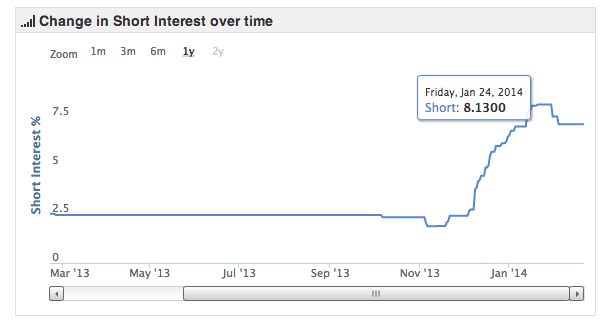

Case Study: Blinkx - beware of short interest surges

This video search glamour stock rose substantially over the year to November 2013 from 38p to 150p. The short interest had hovered at the low 2% level during most of the rise, but when the stock rocketed in December to beyond the 200p level the shorts became aggressive. Short interest surged to 10% over the course of less than a month. On January 30th a Harvard Academic published a critical blog, the stock tanked 40% in a day and the shorts made off like bandits. Complacent shareholders who hadn’t noticed the crucial Smart Money Signal were horribly burned.

2. Days to Cover

Given the potential for infinite losses when stocks rise instead of fall, short sellers really hate being stuck in a position going against them that they can’t unwind. If the share price rises, their losses can escalate to a point where they are forced to buy back shares at a loss. This buying pressure can force other short sellers to unwind too, creating what’s called a ‘short squeeze’. A simple ballpark measure of this short squeeze risk is given by the number of days it would take for all the shorts to unwind (cover) their positions.

The Days to Cover metric is worked out by dividing the number of shorted shares outstanding with the stock’s average daily trading volume. For example if Company X has 10 million shares held short and an average daily trading volume of 2 million - its Days to Cover is 5, meaning that it would take 5 days for all those shorts to be covered.

Analysts use this ratio to measure the sentiment around a stock. The higher the Days to Cover, the more likely it is that short sellers will act to avoid further losses and the more extreme a short squeeze is likely to be.

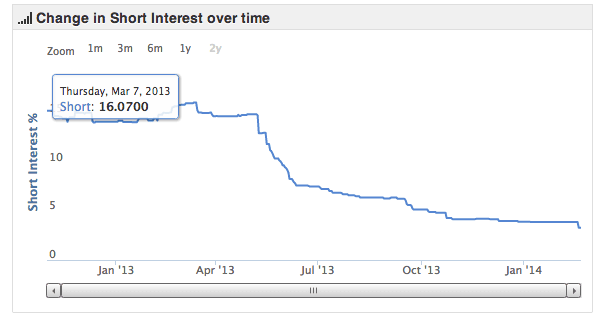

Case Study: How a short squeeze can unfold - Ocado

An example of shorts getting burned occurred in 2013 with supermarket delivery group Ocado. With its sole Waitrose contract, Ocado came to market in 2010 at a flotation price of 180p, which some analysts felt was a bit much even then. By March 2013 it was one of the most heavily shorted stocks in the market, with around 15% of its shares out on loan - a huge number. But that same month Ocado bagged a delivery deal with Morrisons that helped to drive its price up by 200% through the year. The massive price hike was magnified by this big unwinding of short positions, leaving just under 4% of Ocado’s stock on their books at the end of the run.

While short sellers are famously smart sellers, they do occasionally get it wrong and rising prices can be justified. A short squeeze can be the first sign that a company’s fortunes might be changing and that sentiment towards it is warming. For the long-only investor, it can represent a bullish signal and the chance to profit from a likely rally caused by a shake-out that has short sellers running for the exit.

But there is a need for caution. While short sellers can make the wrong call, they can also be the victims of temporarily irrational markets. Be warned: increasingly exuberant markets - as seen since the 2009 stock market crash - can disguise all sorts of ‘nasties’. In these circumstances stock prices can become overstretched as confidence grows and money flows into the market. As a result, junk stocks can become expensive and defy the expectations of short sellers for protracted periods. The question is, when sentiment changes and short sellers are proved right, do you want to be left holding the baby?

How to take short selling signals further

While short interest and Days to Cover are very useful indicators, they don’t always work and sometimes give conflicting signals. As is so often the case with financial metrics, they become even more powerful when used in conjunction with other indicators.

1. Measure how much conviction the shorts really have

Short interest really only tells you one side of the short selling story, and that’s how much demand there is to short the stock. It doesn’t tell you anything about the supply of shares that are available to short.

The supply of stock available to short sellers can be worked out by measuring how much of it is owned by institutional investors. This is simply because short sellers typically borrow their stock from big institutional owners. Shares become particularly vulnerable to a fall when very high short interest combines with low institutional ownership. Shorting these particular stocks needs strong conviction on the part of short sellers because the tight supply forces up the cost of borrowing them.

Analysis by academic researchers of shares over the period 1988-2002 found that the very highest constrained shares performed particularly badly on a monthly basis[2]. For long-only investors, these findings have some pretty stark conclusions: namely that they should avoid shares that are being shorted when institutional ownership is low.

2. Measure how complacent the analyst community is

Like short sellers, research analysts are some of the most informed players in stock market investing, particularly because they have good access to company management.

Yet, surprisingly, there’s evidence that the two sides often reach opposite conclusions from the information available to them. Analysts have a tendency to issue positive notes about the stocks they cover, perhaps as a result of being lured by the prospect of lucrative investment banking work in the future. By contrast, short sellers are entirely bearish about the shares they target and scrutinise fundamentals and valuations carefully before placing bets with client funds.

Work by a team of US researchers in 2010 investigated whether the differing opinions of analysts and short sellers could ever predict which way a share price would move[3]. Incredibly, the results showed that when a heavily shorted stock was highly rated by analysts, the analysts had made the wrong call. This means it makes sense for investors to sell, short or avoid shares with the best broker recommendations but the highest levels of short interest.

3. Measure the direction of change of the shorts

In all things stock market related, price momentum is a critical factor. Rapidly rising short interest, as we saw in the Blinkx case study, can highlight serious flaws in a stock which might have been missed by traditional fundamental analysis. On the other side, falling short interest may indicate a stock where the shorts are rushing to unwind their positions, adding to buying pressure and potentially magnifying the reasons for holding your shares.

All of these factors, as well as the volatility of a stock, can be used in conjunction to provide more accurate metrics.

4. Measure how volatile the company’s share price is

Heavily shorted stocks with relatively high medium- and long-term price volatility (often found with smaller shares) are also more susceptible to the types of large price movements that can cause a short squeeze. In these cases, heavily shorted, highly volatile shares that are experiencing a downward trend in price can periodically see very sharp upward price spikes. These have the potential to panic short sellers out of their trades.

Summary - How you can profit from short selling signals

With some of the most powerful research to hand, short sellers serve a useful role in finding potentially problematic shares. Their actions can be a useful counter-weight to irrational market confidence that keeps share prices in check. As respected analyst and economist James Montier, observed:

Short sellers have been vilified pretty much since time immemorial. This has always struck me as strange, the equivalent of punishing the detective rather than the criminal.

Observing the actions of some of the smartest and best informed investors in the market can offer a substantial edge. In summary:

Rule 1: Stocks being heavily short sold are best avoided by investors. They tend to underperform, especially when there’s also low institutional ownership.

Rule 2: Just a little short interest shouldn’t worry you.

Rule 3: When the brokers say buy, but the shorts don’t agree, it’s worth trusting the shorts.

Rule 4: When short sellers are being ‘squeezed’ and short interest is falling, the company outlook might have improved and the price may rally hard.

While traders with spread betting or CFD accounts have the option of joining short sellers in their battles against the bulls, most investors will benefit from understanding what short data really means. Armed with this knowledge, they can protect themselves from share price falls and profit from short squeezes.

- Ekkehart Boehmer, Zsuzsa R. Huszar and Bradford D. Jordan. The good news in short interest.

- Paul Asquith, Parag A. Pathak and Jay R. Ritter. Short interest, institutional ownership, and stock returns.

- Michael S. Drake, Lynn Rees and Edward P. Swanson. Should Investors Follow the Prophets or the Bears?.