Deep Value: the stock market strategy for the brave

Imagine you're offered $1 for 50¢ - would you take it? Welcome to the world of deep value investing: where you try to buy stocks at a significant discount to their intrinsic value.

It sounds simple, but nothing ever is. The $1 note might be torn, and a bit inky. Your friends may warn you it's not even legal tender. Beyond that, parting with 50 cents today can seem tough if the wait to receive $1 is uncertain. Herein lies the problem. Mr Market may offer you a stock market bargain because he’s depressed, but there’s no guarantee that he’ll get excited again in the future. Perhaps this piece can help you find the patience, tenacity, courage, and contrarianism to take the deal. These are the traits you’ll need.

In this article we’re going to dive deep into Deep Value. Read on and you’ll learn:

The history of Deep Value investing and some of the luminaries gracing the field

The financial ratios and screening approaches needed to find these stocks

The risks and limitations that the canny investor needs to be aware of

The best books to read to further your knowledge.

Is Deep Value the right investment style for you?

This is a game custom-made for the brave and contrarian individual investor. It’s a game that the professional investor struggles to play, as so often the cards that are dealt out are small caps. Typically, stocks get cheap when the share price falls dramatically. As a result, the “liquidity” in the stock dries up.

As passive indexing has grown in popularity, mega passive index funds like Vanguard now manage trillions. Pressure on fees continues, forcing active funds to get larger and larger to compete. This leaves a dearth of professional investors hunting in the small and micro cap areas of the market. They just can’t play in this game, leaving opportunity for the bold individual investor.

Of course, tight liquidity is a double-edged sword. It’s hard to buy positions in illiquid stocks, and it can be hard to get out when markets fall. So nobody should play in this game with money they need in the short term or that they can’t afford to lose.

The opportunities offset these issues. In spite of periods of underperformance, Deep Value investing is one of the most consistent return sources in markets. But it’s not easy work, requires a keen interest in the financial statements, and tests the mettle of even the hardiest investor.

Some background on Deep Value Investing

Warren Buffett once wrote an article titled "The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville" in which he mocked the idea that stock market results were random. He said you could compare the investments world’s results to the outcome of 225 million Americans having a coin-flipping contest. At the end of 20 winning flips, there would be only 215 Americans still standing. If stock markets were random, how statistically likely would it be that 40 of them came from the same geographical origin?

I think you will find that a disproportionate number of successful coin-flippers in the investment world came from a very small intellectual village that could be called Graham and Doddsville. Warren Buffett

The investment philosophy of our successful coin-flippers, which included Buffett, Walter Schloss, Bill Ruane, Charlie Munger, and many more, came from Buffett’s tutor - Benjamin Graham, popularly known as “the father of value investing”.

Graham had an almost financially fatal experience in the Great Crash of 1929. He had gone into this period with high leverage, learned the lesson, and only clawed his losses back in 1935. In “Security Analysis”, first published in 1934 with David Dodd, he outlined his conservative methods of buying stocks with a Margin of Safety - ensuring either significant asset backing or significant earning power over and above the price paid. In principle, if you buy a stock at a price that gives you such a margin of safety over its true intrinsic value then, on average, Graham would expect your results to be quite “satisfactory”.

Buy Cigar Butts for “one last puff of profit”

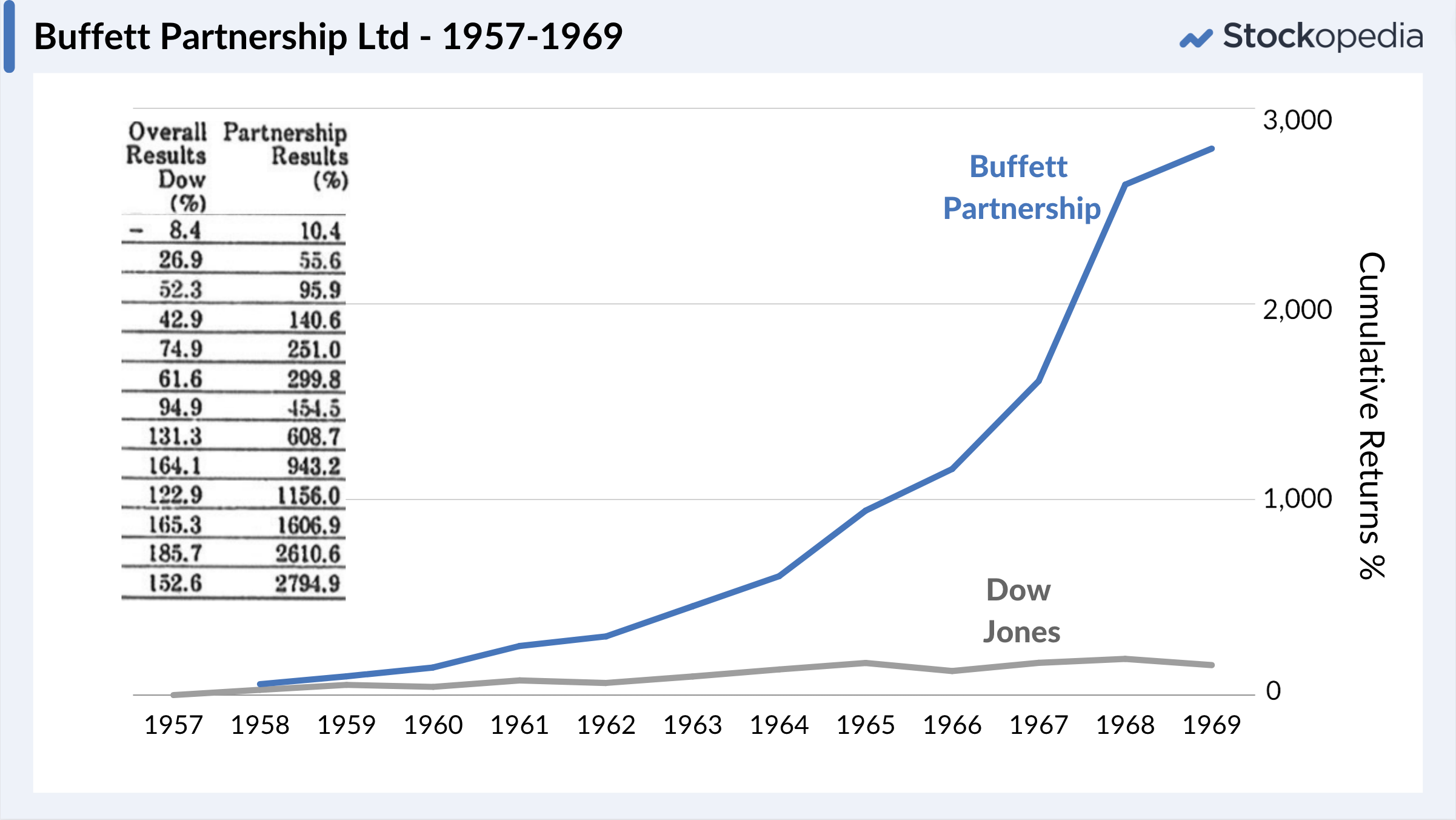

Buffett may be well-known today for investing in big quality, consumer companies like Apple, Coke and Amex, but his first decades in investing were spent hunting for “cigar butts” - bargain stocks that had “one last puff of pure profit”. He used Ben Graham’s “net net” techniques (described below) to find them, and averaged 29.5% in annualised returns over the 13 year period of his original Buffett Partnership.

He would often take highly concentrated stakes in companies, much as an activist investor these days would do, and either wait for the stock to revalue because the majority owners did something about it, or take a controlling seat on the board to reshape the company. The problem for Buffett, was that his partnership grew too large. He was so successful at playing the bargain stock game in small caps that he ran out of opportunities. He eventually wound down the partnership. This type of deep value investing is not a strategy that scales.

Cigar butt investing was scalable only to a point. With large sums it would never work well. Warren Buffett

But there were others, such as Walter Schloss, that took a broader approach. He never tried to get to know the stocks he invested in. He never met the management. He didn’t concentrate his investments like Buffett, he generally owned smaller positions in more than 100 stocks. He simply bought when their valuations were too low, and that’s all he did. His partnership compounded returns at 21% for 28 years, owning more than 800 stocks over the period. There’s more than one way to skin a cat.

Didn’t all the bargains dry up?

Many may protest that “it was easy back then, the opportunities have now dried up” and erroneously point to Warren Buffett moving on as evidence. It’s true, in those markets, buying bargain stocks was easy if you did the work. But the profits to Deep Value are still available to the few who still hunt for them.

Adventurous investors often look internationally when their own markets get pricey. When Peter Cundill took over the struggling All Canadian Venture Fund in 1975, he changed its mandate to hunt for global Bargain stocks according to Ben Graham’s rules. Between 1975 and 2010, the rebranded Cundill Value Fund generated 13.7% annualised returns. The opportunities are out there.

How to identify Deep Value stocks

There are many ways of hunting for bargain stocks. We’re going to look at a couple of approaches, firstly the classic Ben Graham “Net Net” stock evaluation, followed by the Acquirer’s Multiple approach more recently popularised by Toby Carlisle.

Method 1. Ben Graham “Net-Net” Bargains

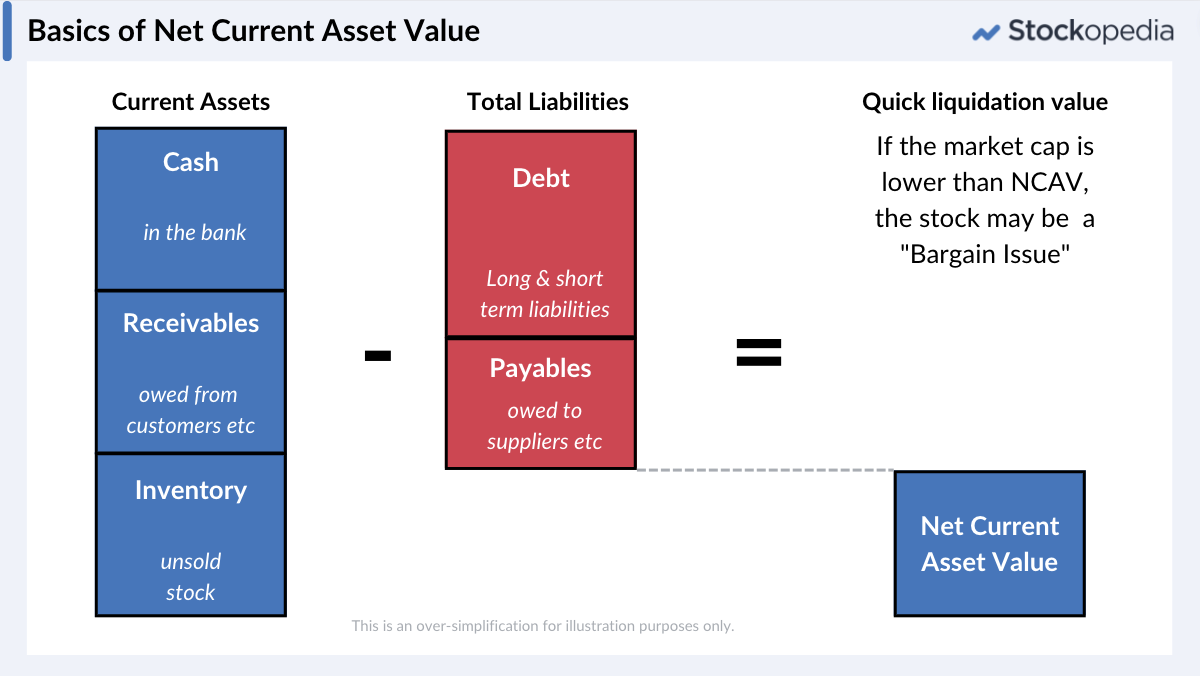

Having been burned in the Great Crash of 1929 and the following depression, Graham laid out a simple framework for enterprising investors to identify “Bargain Issues”. His theory was grounded in the idea of assessing “liquidation value” to ensure he had downside protection if the company ever went bust. In a liquidation process, administrators would sell off everything the company owned and pay off everyone it owed. He wanted to make sure that even in that worst case scenario, he’d make a profit.

Of course, some assets are more “liquid” than others. Cash equivalents, money owed from customers yet to pay, and unsold stock on the shelves (together known as current assets) can normally be turned into cash pretty quickly. But property, factories and equipment could take a lot more time to sell, in some cases years.

Graham wondered - what if you could pay off all the company’s debts just from the current assets alone? In that scenario, you’d receive all the property, factories and equipment for free. So he created a measure of this called the “Net Current Asset Value”. Some call it “Net Working Capital”. The basics of calculating this are illustrated in the diagram below.

Graham thought - what if you could buy shares in a company for less than Net Current Asset Value? If the company still had a business, and still had earning power for the future, it could be trading way too cheap.

This is the basis for one of Deep Value’s greatest financial ratios - the Price to Net Current Asset Value (P/NCAV). Ben Graham, Warren Buffett, Peter Cundill and many other Deep Value investors have searched for shares trading at below liquidation value, either at a P/NCAV of less than one or an even steeper discount.

Early in his career, Ben Graham liked to discount the value of the current assets even further, for a deeper “margin of safety” in case the value of receivables and inventory couldn’t be recovered in full. This became known as the Net Net Working Capital approach - which is where the term “net-net” comes from. But studies have shown that there isn’t much extra to be gained from discounting current assets that far. So most people screen for a P/NCAV < 1 rather than use the stricter P/NNWC < 1.

Many published studies of net-net investing have shown 20-35%+ annualised returns over different decades, and internationally. Anyone interested in validating this can use the links at the bottom of the article which map out studies by Joel Greenblatt, Henry Oppenheimer and more.

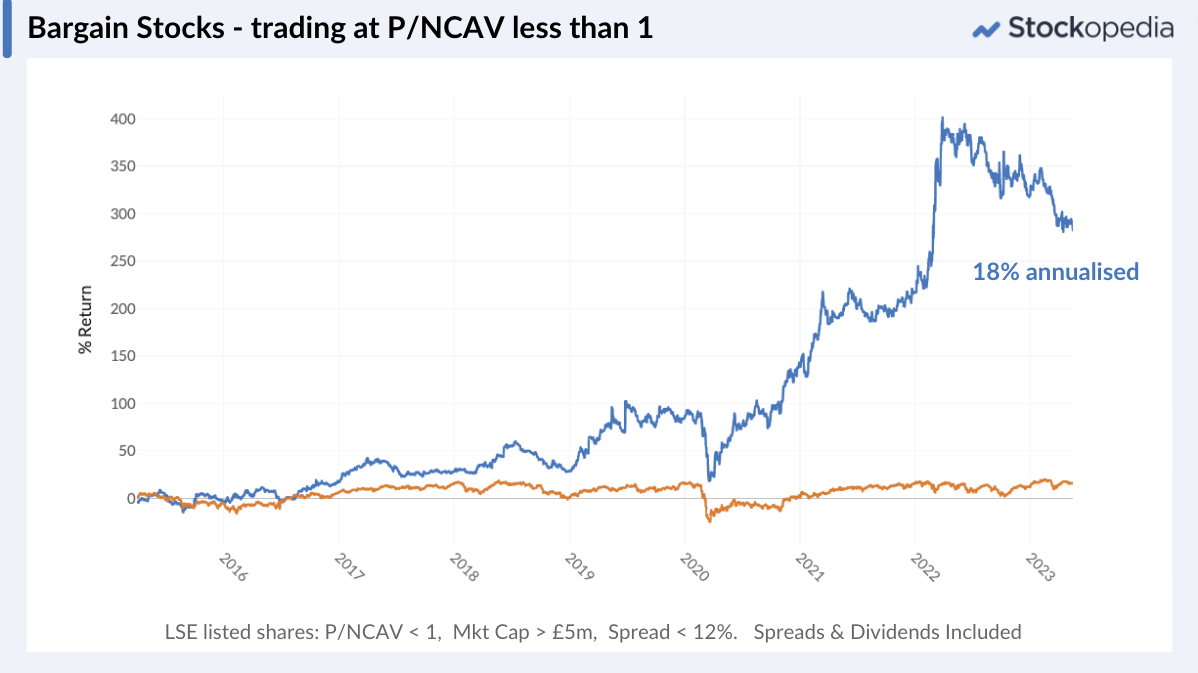

Our own tracking at Stockopedia.com has shown the profitability of this strategy in most markets. The below chart illustrates the simple returns to a P/NCAV < 1 portfolio, annually rebalanced with an 18% annualised return (inclusive of spreads and dividends). We cut out the tiniest stocks, Mkt Cap < £5m, but returns are even higher if they are included. We also provide a pre-rolled Graham NCAV Bargain Screen and other Bargain stock screens in the Browse section.

Most net-net investors, especially if investing on a concentrated basis, do tend to introduce some further financial checks and qualitative research into their approach. Here’s a few items to investigate:

Watch out for excessive debt. Graham and Buffett would always try to minimise the risk of default by ensuring a strong balance sheet. There’s no hard rule, but Net Debt to Equity (Net Gearing) higher than 50% is worth reviewing.

Confirm the company has a history of earnings and dividends. There’s no evidence that currently loss making net-nets do worse than profitable net-nets, but checking the history can help filter out companies that may not return to, or have ever had, “earning power”.

Beware of declining current assets. Companies may already be liquidating their current assets internally. This can be a red flag, so check the balance sheet from one year to the next. Ensuring a Current Ratio of more than 1.5 can give some confidence in that current liabilities can be paid off by current assets.

Insider and activist investor activity - If there’s strong insider ownership and purchasing of shares, it is likely they will be working in your interest as a shareholder. Evidence of outside activist investor interest is even better. (Check the Major Shareholders and Directors Deals activity).

We’ll talk more about some other checklist items below, especially regarding the issues around dealing liquidity.

Method 2. Buy the bargains most likely to be acquired

Warren Buffett outgrew his bargain hunting days, and graduated to investing in “wonderful companies at fair prices”. He made this transition with aplomb. His folksy style attracted millions of investors to the “Compounding Quality” style of investing - another style explored in our Strategy Map.

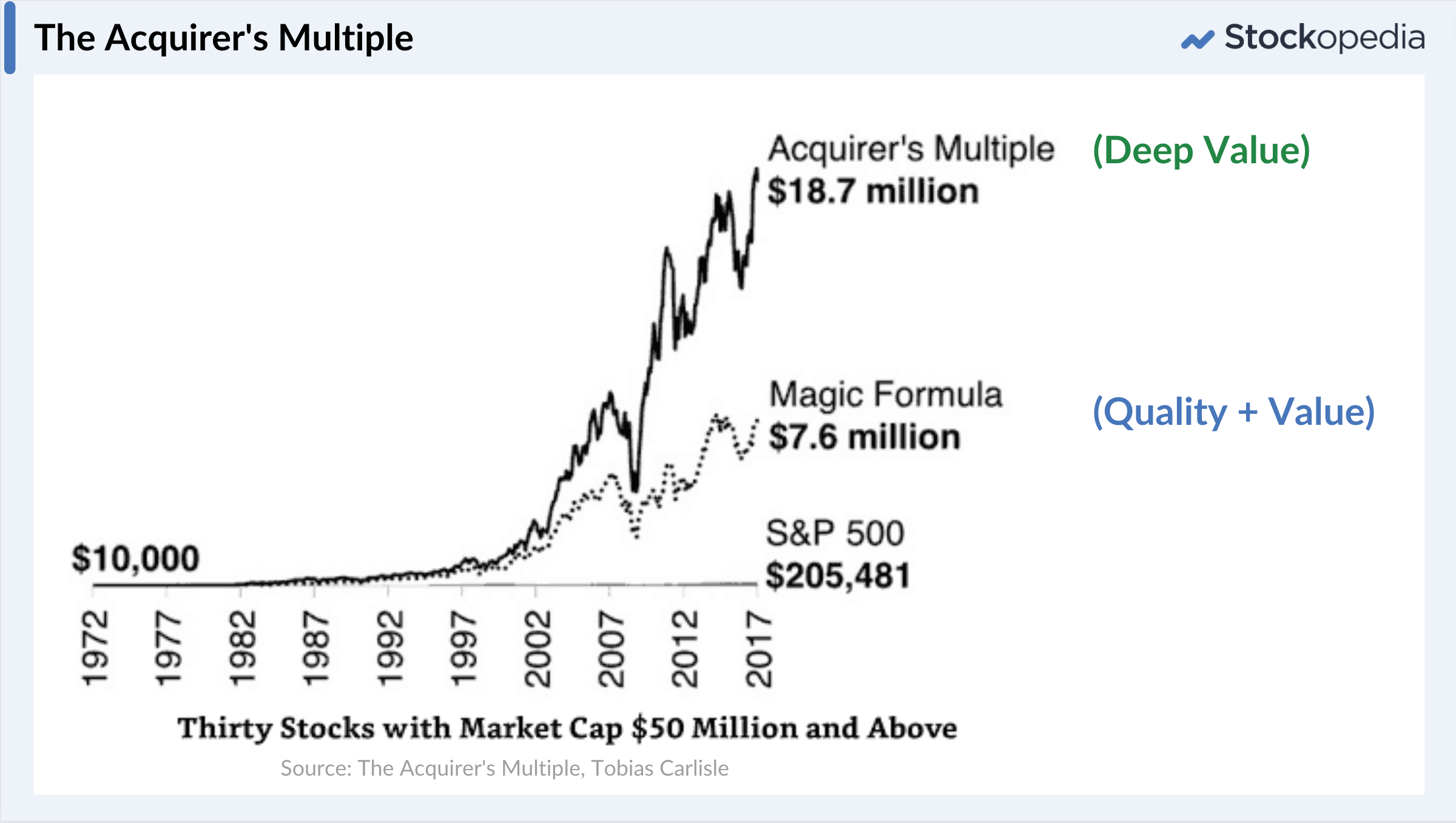

But Tobias Carlisle challenges Quality stocks in his excellent book “The Acquirer’s Multiple - How the Billionaire Contrarians of Deep Value Beat the Market”. Highly profitable stocks attract competition, which reduces their margins, and brings their valuations down. Nobody has yet figured out how to quantitatively assess whether a company has an enduring competitive advantage. Picking great businesses is harder than it seems.

Carlisle offers the answer. “Buy fair companies at wonderful prices”. These companies are more likely to recover their profitability than quality companies are likely to sustain them. They are also bid targets which can be a catalyst to a revaluation. To identify them, you need to understand how acquirers think.

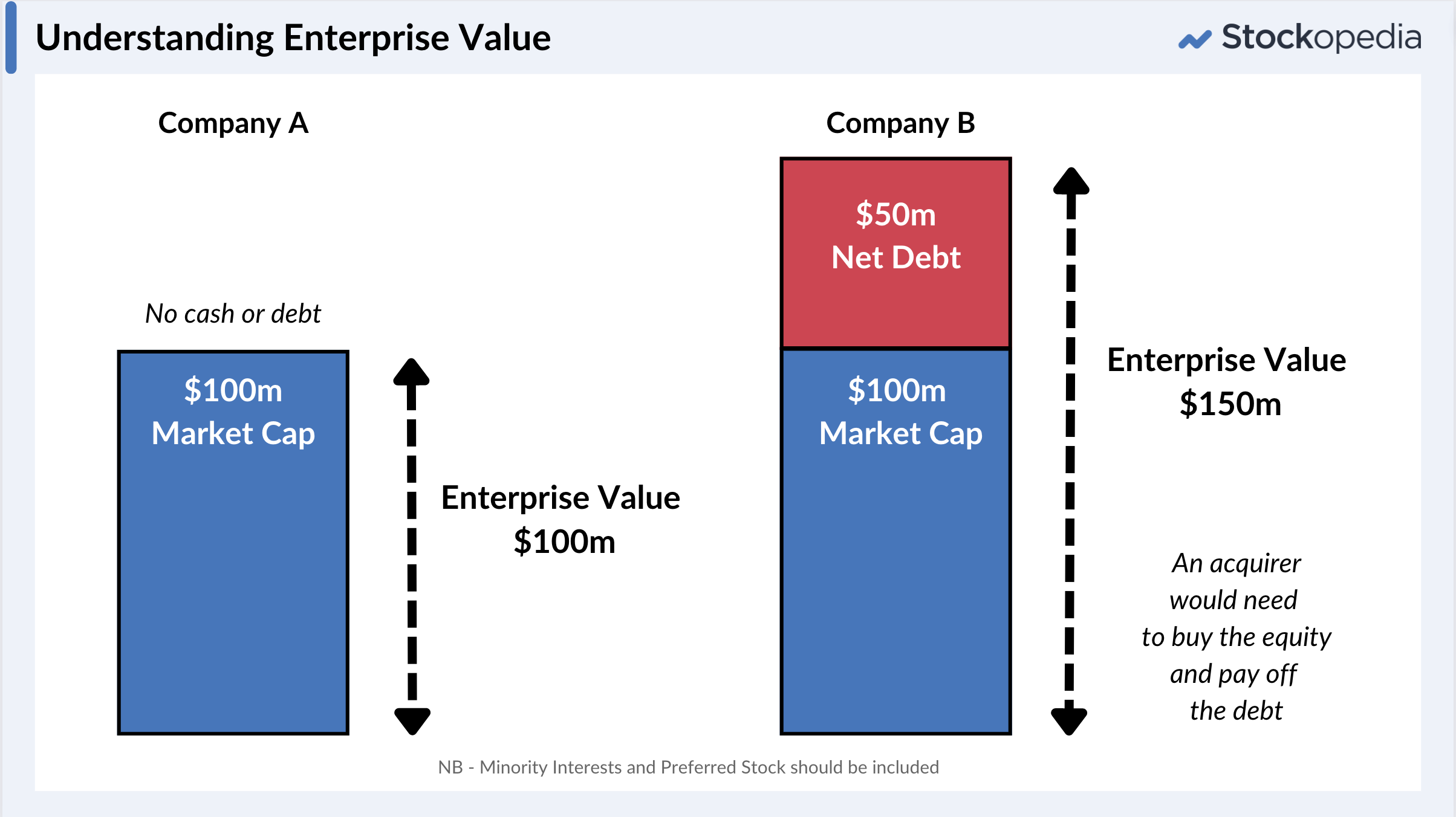

If you were an acquirer, you would buy the whole business, not just a few shares. So you also take on the company’s debt. Imagine two companies trading at a £100m market cap. Company A has no debt, Company B has £50m. If you buy Company B you are still liable for that £50m. The “Enterprise Value” of Company B is £150m, £50m more than Company A. So factor that in.

If you bought the company, you’d also want to know it was yielding good cashflow and profits. To do so, it’s best to look at Operating Profits - earnings before tax, interest and other claims.

The Acquirer’s Multiple is calculated as Enterprise Value / Operating Profits. It’s how many years it would take for the price you paid (the enterprise value) to be covered by operating profits. You want this to be as low as possible. You can think of it as a better version of the P/E Ratio - often known as the “Earnings Multiple”. The P/E ratio has little use to an acquirer, as it doesn’t factor in the net debt.

Carlisle backtested portfolios of 30 stocks, annually rebalanced, that were the cheapest in the market by this measure. He wanted to know if pure “cheap” stocks beat not only the market, but also “cheap and good” stocks. His results were impressive, with the portfolio compounding at 18.6% annually over 44 years. We haven’t replicated such high returns with this approach, but have seen 10% annualised results since 2015 in the UK.

While we don’t publish the exact Acquirer’s Multiple, we do publish the EV / Operating Profit which is a close analogue and the same for the majority of companies. It’s easy to sort the market by this metric. You can view an example screen here.

Why does Bargain Investing work?

It’s simple, the market overreacts on the downside when companies have problems. Fund managers don't want to be seen owning a dog, so they sell it. That selling leads to undervaluation and often leads to neglect, as analysts and brokers give up covering the stock. Entire sectors can end up in decline when, for good reason, their profits and profitability take a nosedive due to technological disruption, competition, or other reasons.

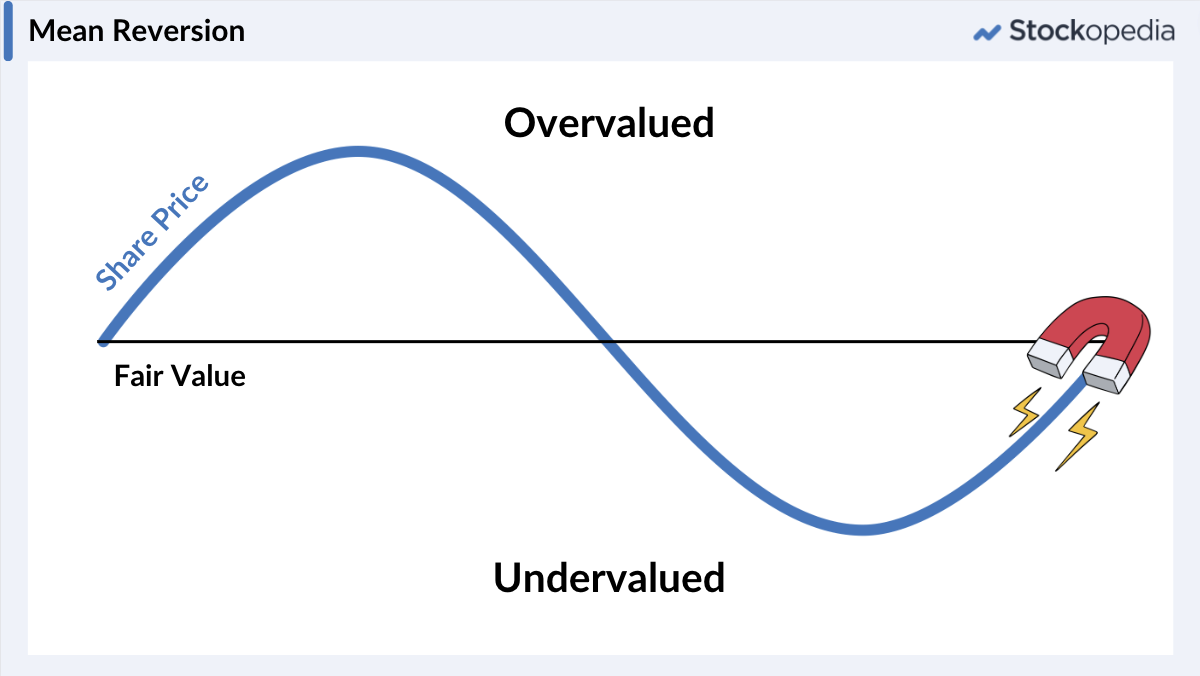

But what's remarkable is that valuations do not tend to stay cheap forever. Mr Market eventually figures out the true valuation and reprices assets. The key principle behind value investing is this - valuations revert to the mean.

Mean reversion acts not only on the valuation of companies but also on their profitability. Cheap companies still have businesses and assets. New management changes in the operation can often lead to profitability being revitalised or for the assets being sold off to make a return. Company insiders buy shares. Activist investors step in and bid. Fair value is like a magnet. It eventually pulls share prices back towards fair value.

Challenges for Deep Value Investors

There are a range of challenges common to all deep value strategies, and it’s worth generalising some approaches to dealing with them. When you review the stocks on a Deep Value list, you are going to have to prepare for some visceral personal reactions. Let’s take a look at some ways to deal with this.

1. “These companies are going bust”

Whenever anyone looks at a deep value stock, they see a company with problems. Debt, troubled business models, worries over receivables and more. While Warren Buffett early in his career, or corporate raiders in more recent times, could go in and sort out the issues themselves (through restructuring or other routes) that’s not a viable option for the private investor. You don’t want to be left holding the bag. Screening for Net Gearing < 50% can help cut out the highly indebted stocks, but how to stop worrying about permanent capital loss?

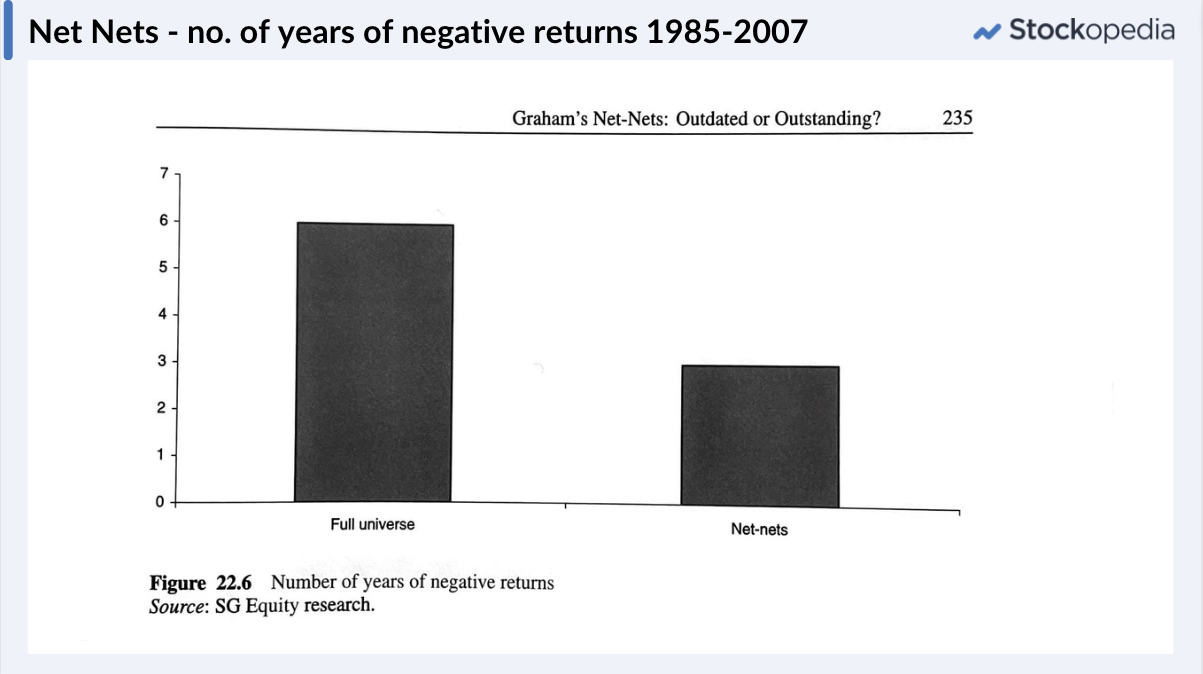

A study by James Montier in 2008 “Graham’s net nets, Outdated or Outstanding?” soothes this concern. In his 22-year study, he illustrated that the overall universe saw 2% of stocks suffering a permanent loss of capital (i.e. bust), versus 5% for net-nets. But he also showed that on average, net-nets only suffered three down years (at a 35% annual return) versus six (at a 15% annual return) for the overall market. Montier concluded that most investors avoid net-net stocks as they narrowly frame their attention on each individual share’s troubles, rather than the benefits of owning the broader basket. Focus on the power of the group, rather than the weakness of each individual stock.

2. “The company is too small or illiquid to buy“

No doubt about it, most deep value stocks are tiny. Montier’s 2008 study indicated that the typical global net-net had only $21m of market capitalisation. What’s particularly difficult is small-caps like these have very wide “Bid-Ask Spreads”. This is the margin between the buy price and the sell price. It’s not unusual to see stocks with 5%-15% spreads or at extremes as much as 50%. That’s a painful price to pay on purchase. The good news is that you can screen out the most illiquid extremes (say < 15%), and set limit orders with your broker to try to buy within the spread. If you are trying to buy a large position (in a large portfolio), you may have to edge in over time, dealing patiently day after day. This takes persistence, though remember, you aren’t going to get out quick if you get in slow.

3. “The company is at the top of its cycle”

This is a regular concern. Some companies in deep value screens can be “cyclicals” at the top of their earning cycle. They do very well when the going is good in their industry, but poorly when the going is bad. The market often prices these companies cheaper when the going is good, and expensively when the going is bad, as they expect earnings to fall or rise in the future respectively.

In the UK, there are regularly a lot of house-builders qualifying as “net nets”. The market is often skeptical that their profits are sustainable. Ben Graham suggested using the Price to Average Earnings Ratio as an additional filter - an average over 6 or 10 years. This has become known as the CAPE ratio (cyclically adjusted PE Ratio). Graham suggested setting a cutoff at a CAPE < 16. This regularly cuts out some of the net-nets on the list that might actually be expensive at other times in their business cycle.

You can screen on the CAPE for 3 year, 6 year and 10 year variations using Stockopedia’s database as an additional filter.

4. “These are loss makers, burning cash”

Some stocks which come up on Ben Graham screens can have their only current asset being cash. I’ve regularly seen biotechs in this vein. So they are cash burners. The issue is they often don’t have any viable historic or near-term future earning power. Ben Graham would instantly dismiss these, but the jury on loss making bargains is still out.

Henry Oppenheimer did a famous study on net-nets in 1986 that actually showed that loss making net-nets outperformed profitable net-nets, and that non-dividend paying net-nets outperformed dividend paying net-nets. As Ben Graham has said, even an inferior asset can become an “investment”, rather than a speculation at the right price.

It all comes down to an individuals comfort for risk, but also their approach to portfolio management. While I’d never be comfortable with an entire portfolio of loss makers, holding a few is absolutely fine if you know the price is right.

Running a Deep Value Portfolio

Should you concentrate or diversify broadly?

This does depend on your mindset. Walter Schloss or John Templeton would buy 100 stocks or more. Warren Buffett would put more than 25% of his portfolio in a single stock. The difference was the level of research that Buffett put into his purchases. He also regularly got heavily involved with the management of the stocks he bought.

If you are a full-time investor, and genuinely know what you are doing, you may well be able to run an effective concentrated portfolio with 8–10 stocks, but for the rest of us, owning a minimum of 16-20 deep value stocks is prudent. Joel Greenblatt, author of a classic bargain stock study “How the Small Investor Can Beat the Market”, himself advocated owning 20–30 stocks if you were buying stocks in groups.

One thing to be aware of is sector concentration in your screening results. I’ve regularly seen big skews to certain sectors on net-net screens. Sectors can get deeply out of favour, especially when cyclicals are shunned. You must avoid taking a “single sector bet” - so factor that into your portfolio construction approach and enforce a spread across sectors.

How long should you hold onto the stocks for?

Various studies into net-nets have shown that the optimal holding period is about a year. The longer positions are held beyond a year, the lower the annualised returns may be. That doesn’t mean systematically buying and selling your whole portfolio on the same day, you must use your judgement in managing a portfolio of illiquid stocks. Of course, dealing costs do come into it. Some net-net investors encourage selling either on a 100% gain, or after 2 years. Beyond this, the opportunity cost becomes too great.

Over to you… the bargains are out there

It’s at the bottom of bear markets that bargain stocks really shine. Back in 2009, James Montier started to see names like Microsoft, BP, Novartis and Sony show up on his Deep Value screens. It’s during times like those, that “loading up” on bargain stocks makes the most sense, as they can often be high-quality names with significant earning power. The returns from bear market lows can be stunning.

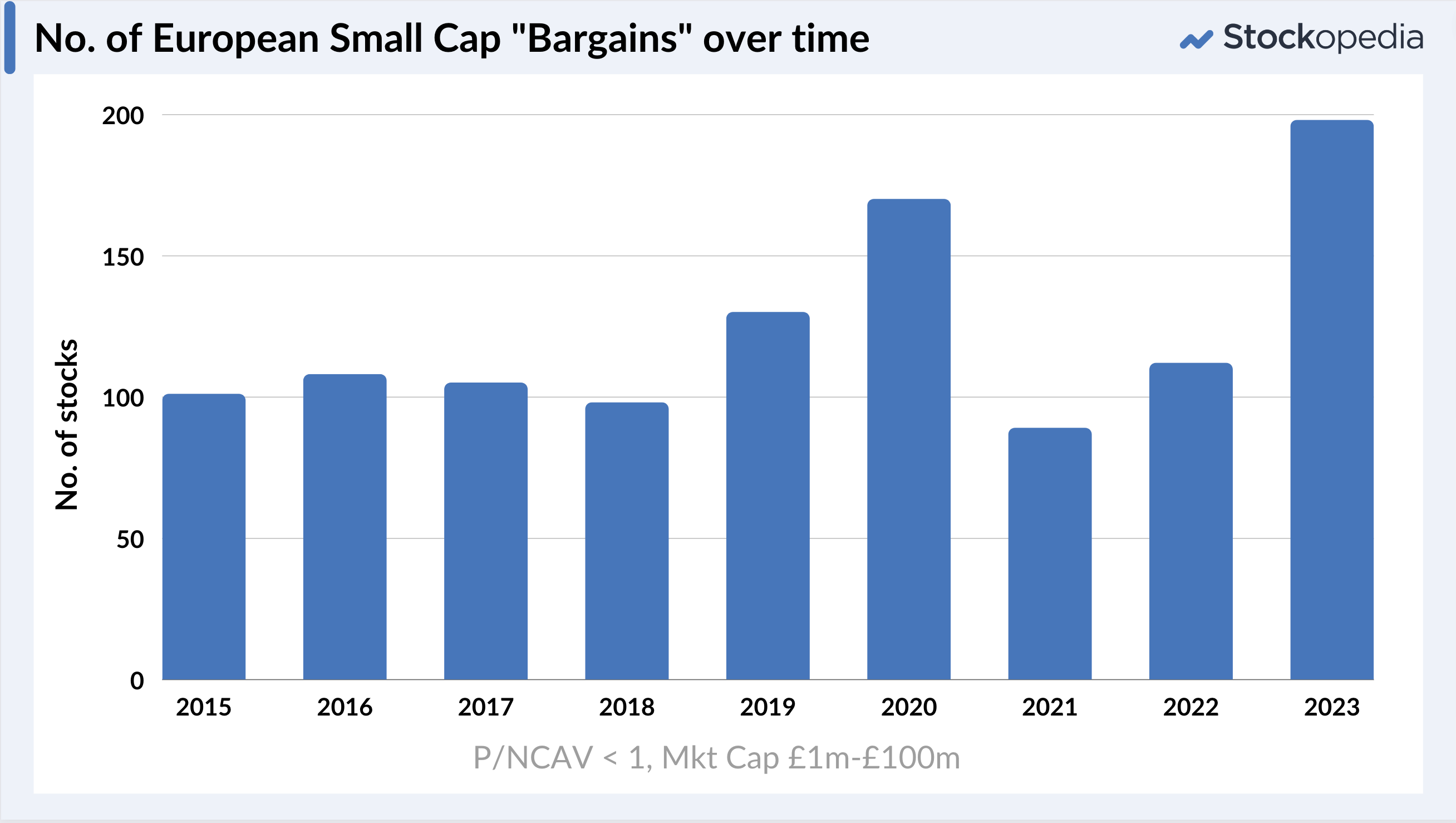

Our own market studies show that the number of “Ben Graham Bargains” changes through time. When the market is going through difficulties, there are many more - such as during the height of the pandemic crash - but there is a persistent flow of bargain stocks across the market cycle.

At the time of writing, between a £1m and £100m market cap, there are 171 sub working capital bargains in Developed Europe, 41 in the UK, 282 in the US (a lot of these are Chinese), 52 in Australia, 115 in India, and 232 in Japan (long known as the land of bargains)… I could go on. The bargains are out there.

Recommended Reading

The Intelligent Investor - Ben Graham (or Security Analysis for more detail)

Value Investing - James Montier (good sections on net-nets)

The Acquirer’s Multiple - Tobias Carlisle (great little summary)

There’s Always Something To Do, The Peter Cundill Investment Approach - Risso Gill

Net Net Stock Strategy - Evan Blecker - (the best book on net nets)

Deep Value Investing - Jeroen Bos (uk bargain stock fund manager stories)